![By Illustrator unknown [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/32/Blind_men_and_elephant.jpg/387px-Blind_men_and_elephant.jpg) As part of our efforts here in BC around Open Textbooks, I have asked those involved with the project to single out some of their favourite examples. You see, when we use the term “open textbooks” we all think we know what we mean by it, but like the blind men and the elephant, depending on your perspective, “open textbooks” can end up meaning many things, and so it felt like being able to point to specifics would be helpful.

As part of our efforts here in BC around Open Textbooks, I have asked those involved with the project to single out some of their favourite examples. You see, when we use the term “open textbooks” we all think we know what we mean by it, but like the blind men and the elephant, depending on your perspective, “open textbooks” can end up meaning many things, and so it felt like being able to point to specifics would be helpful.

For many, “open textbooks” seem to be primarily about cost savings, about saving money for both funders and learners, but not particularly about challenging the “form” of what we have known as a textbook. And I agree, affordability is a strong motivator to get into this space, and an obvious selling point for all the stakeholders (well, almost all – commercial publishers don’t seem exactly thrilled about it.)

But the need to save money is not the only force shaping the future of textbooks.

It is impossible to ignore the rise of eBooks, especially since Apple has decided to disrupt this market too.

Add to that all that we have learned over the years about the important affordances of the digital (copy-ability, fork-ability, remix-ability, interactivity and rich media) the network-enabled (discover-ability, collaboration, enabling serendipity, real time-ness) and the mobile (any time, any where).

Add to that questions about whether the model of learning implicit in “textbooks” has become outdated, alongside the explosion in the quantities of information we are experiencing, and it would seem that simply producing cheaper versions of what we currently have in printed textbooks is the very least we could aim for, as big an accomplishment as that would be in the short term.

So given all of that, what indeed should we be aiming for?

An All-eBook Future?

One approach (which with the advent of Apple’s new iBook authoring tool is sure to lure many folks) is to leap directly towards full-on electronic textbooks. Given the recent explosion in sales in both eReaders and eBooks, this looks to many like the future.

And undoubtedly, in part it is. While the sheer number of platforms and packaging formats may give you pause, eBooks are here for the foreseeable future, and offer many of the benefits of being digital and mobile. But not necessarily all of them, or at least the extent to which they enable these is very dependent on the way in which they are implemented. On their own, without some sort of network-based publishing system, eBooks don’t lend themselves that well to collaborative authoring. While plugins like Firefox’s ePub reader make some formats accessible to those without eReader devices, they don’t necessarily serve other populations (offline, disabled) well. They deny the importance of the resale market in textbooks (though this is perhaps not an issue for open textbooks.) While digital note taking and annotation is often trumpted as improved in eBooks, I’m not personally convinced that we’ve made the leap yet in terms of how people study with textbooks.

Are we ready for ALL eBooks all-the-time? Well no, I don’t think so. Will it take 25 more years for the printing press to finally disappear, or less. I don’t know, but my guess is it won’t be the case anytime soon, nor is it even totally desirable.

Wither the Web?

In some ways, eBooks seem actually an answer begged by the question of eBook-specific devices and the whole metaphor of “books as objects.” People have been reading electronic materials even before the dawn of the web, and the rise of the multi-purpose tablet, led by the iPad and quickly followed by many Android-powered devices, seems to me to bode a short future for eReader-specific devices and the many of the formats they’ve spawned.  And what of those eBook formats in general? Even those, when you dig in, most often look like just a packaging format for XHTML/XML content and little more. And with the increased rich media capabilities of modern browsers coupled with HTML5, one is left wondering if there is anything that specific to “eBooks.” Google seemed to question just that when it produced this “20 Things I Learned about the Web” book using only HTML5.

And what of those eBook formats in general? Even those, when you dig in, most often look like just a packaging format for XHTML/XML content and little more. And with the increased rich media capabilities of modern browsers coupled with HTML5, one is left wondering if there is anything that specific to “eBooks.” Google seemed to question just that when it produced this “20 Things I Learned about the Web” book using only HTML5.

In many ways, the book/ebook/web distinction needs to be understood along the same lines as the App/Site distinction and the overall fight for generativity. (As an aside, if you haven’t read it already, please get yourself a copy of Jonathan Zittrain’s The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It [free PDF copy here] to help undestand this term and how it underpins what so many of us are fighting for in the trenches of open source, net neutrality and open content.) On the one hand you have open standards that lead to an explosion of individual freedoms and creativity, and on the other, enclosure, false scarcity and gatekeepers in the guise of “user friendliness.” Of course it is not so simple as that, nor such a clearcut binary. It never is. But given where we’ve got to in the short 20 years of the web, we are foolish to simply abandon it in favour of teh shiny.

The Best of All Worlds?

But do print, the web and eBooks need to be mutually exclusive choices? Emphatically NO! We now have dozens of examples of content that gets authored online, in collaborative spaces, that is usable on the web but also capable of output both as printable books and downloadable eBooks. What has for so long been the promise of first SGML and later XML, to detach content from presentation and allow content to flow seamlessly into various forms, is finally moving out of the realm of the experts and into end-user oriented environments. I will discuss two such approaches in the posts to follow, but there are more showing up every week.

Now a criticism has been made that, when it comes to textbooks, the “user generated” versions are a big step back from the polished versions we’ve come to expect from publishers. To be fair, that article is a couple of years old now, and things move quickly in this space. But at the same time, it’s an important criticism to acknowledge. And for now I think it’s still largely true – the state of open textbooks that are not commercially produced (in saying this I am excepting FlatWorld Knowledge) are mostly not stunning to look at, they lack some of the polish their commercial alternatives have developed. And I think David Wiley is also correct when he argues that currently most open textbooks are only focusing on what’s traditional thought of as the “student edition” of a textbook, and that the supporting materials (problem solutions, lesson plans, teaching tips) are very important to encourage faculty adoption.

But… where have we heard this before? Isn’t it clear by now how much better Encyclopedia Britannica is than Wikipedia? How superior Microsoft apps are to open source versions? This is the perennial charge by incumbents in all sorts of industries towards peer production and openness. To which, a few responses:

But… where have we heard this before? Isn’t it clear by now how much better Encyclopedia Britannica is than Wikipedia? How superior Microsoft apps are to open source versions? This is the perennial charge by incumbents in all sorts of industries towards peer production and openness. To which, a few responses:

- While at first it may be true, given enough people and an important enough goal, it becomes less and less so. cf. Ubuntu, Open Office, etc.

- This is less damaging a critique when the alternative being proposed is not intended as an exact duplication of what it is replacing. So – mediawiki-based textbooks now offer both ePub and PDF outputs as well as the site. But in addition to being collaboratively editable, the “textbook” begins to take on a different role when it is embedded in a collaborative environment that can be used for teaching. And extensions like UBC’s EmbedWiki mean that it even small chunks can flow and intermingle in a way that is synonymous with virality.

- But, and this is critical for me, as important as cost is as a motivator, we frame the discussion about openness and open textbooks as being primarily or solely about cost savings at our peril. Free beer is of little solace when it’s served to those who’ve lost the actual freedoms they’ve struggled to win. The co-evolution of “Good Enough” and open networked collaboration is not simply accidental – we seem slowly to be understanding that the WAY we do things, and the way we structure our relations with each other in producing things, is important, needs to be factored into the “value” of the things produced even if we can’t account for it. There will be an initial hit in terms of productivity, in terms of polish, as we transition, but unless we start to understand this we are all going to keep winning our race to the bottom.

The Process of Change & Innovation

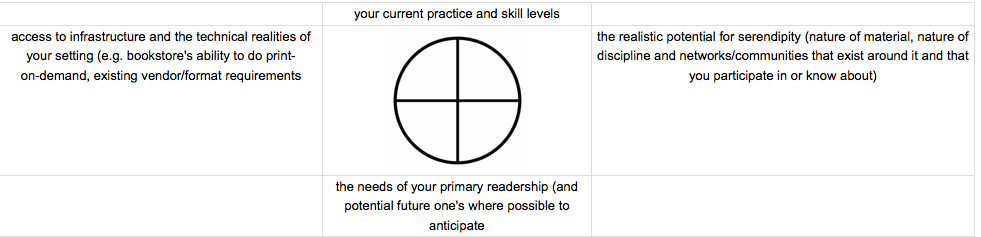

Still, we all have to start somewhere. As described above, there are MANY factors potentially affecting the future of textbooks. One of the challenges we face in our institutions (themselves already by definition resistant to change) is balancing the need to respond to or take advantage of these varied factors with other real constraints. In my upcoming talk on open textbook authoring models and platforms, I try to depict the considerations an individual instructor might need to balance:

and offer some of the questions to ask oneself:

- Who are the authors?

- Who do you expect to read and use the textbook?

- How will they author?

- How they read (format)?

- How they interact?

Ideally, after asking oneself these questions, one would select one of the many, many options now available to you.

But from an organization’s perspective, having limited resources that we need to dedicate to only a very few specific approaches, we need to settle on just a few. Over the next couple of posts I will outline a few that I am investigating in an effort to devise our strategy going forward. Ultimately, the point of this post (other than just trying to work out my own thoughts) was to make clear some of the boundaries I think are important in this decision making. I don’t have the perfect solution, not sure there is such a thing, but I have been doing this long enough to have erred in both directions, to have chosen the exigent over the long term, but also to have anticipated future possibilities over current realities. I can’t say I will never do the same again, but I know I’m even more likely to if I don’t become aware of where these boundaries are. – SWL

Loving this series. Where is this talk you mention going to be delivered?

The talk is online, in elluminate, and a joint contribution to both the 2 week long seminar on eBooks that Rick Schweir is hosting at SCoPE and eCampusAlberta’s regular online professional development series. It will be held at 1:30pm Pacific on Tuesday February 6th at http://bit.ly/yspuFm

Honestly though, you can probably get the gist from my outline at http://bit.ly/zexTMk and save yourself the hour of listening to me talk into the ether (god how I hate elluminate sessions!)

Spot on, Scott. Another great post. I’ve been (I now realise) grappling for the parallel between eBooks and Apps. And you’ve nailed it utterly.

Great post, Scott… but we can’t forget… anything labeled “open” (e.g., “open textbooks) needs to be both free *and* openly licensed (or put in the public domain).

OER (including open textbooks) are teaching, learning, and research materials in any medium that reside in the public domain or have been released under an open license that permits their free use *and* re-purposing by others.

(1) Open license is core to any OER (or open textbook) definition.

(2) Free as in free beer and free as in freedom – need both for “open textbooks.”

Hope to see you soon! I’ll be in Vancouver on May 3.

Cable Green

Director of Global Learning

Creative Commons